Tea, Tech and Trials

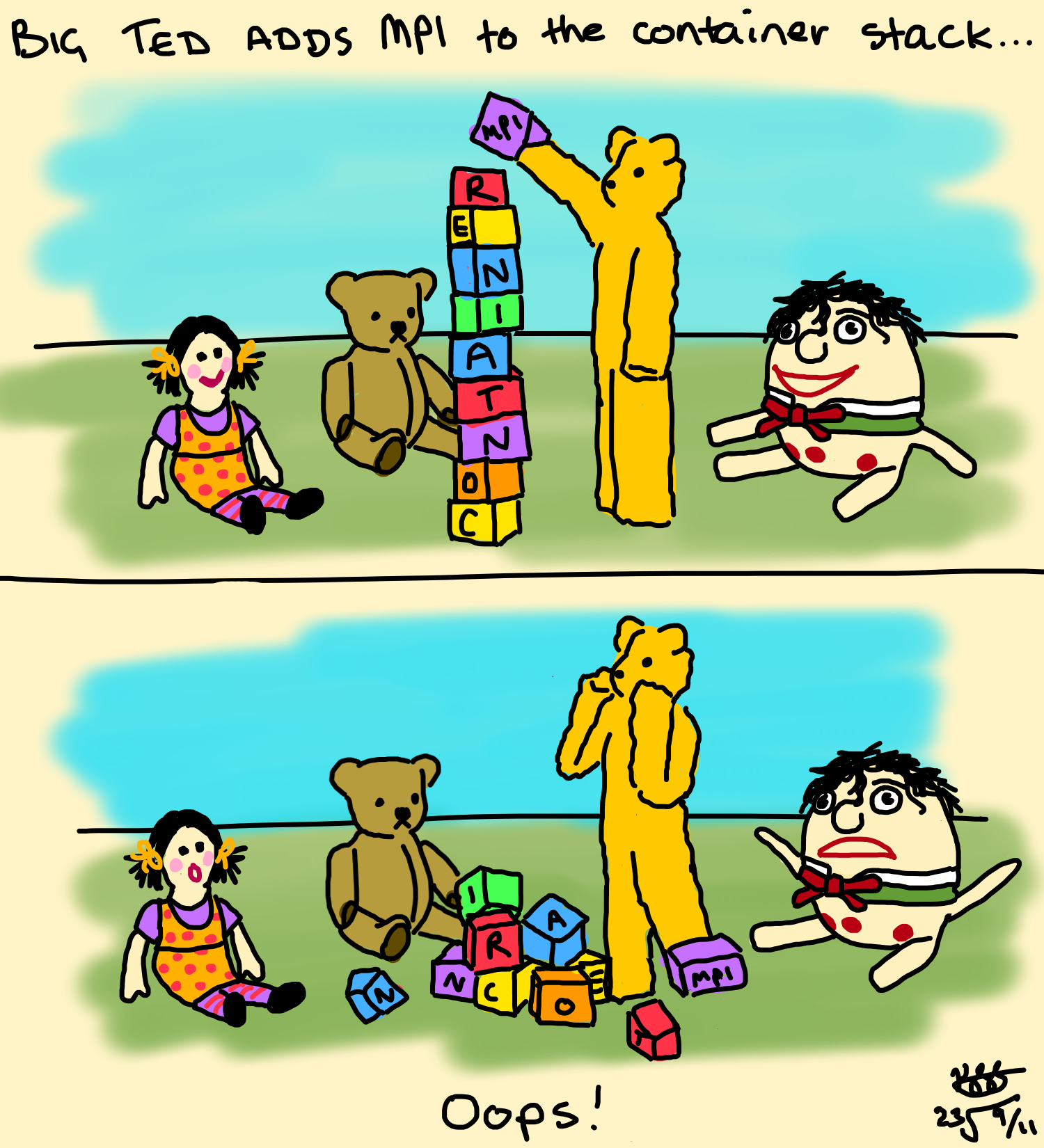

Container builds with MPI

Featuring Playschool!

Published on 09 November 2023.

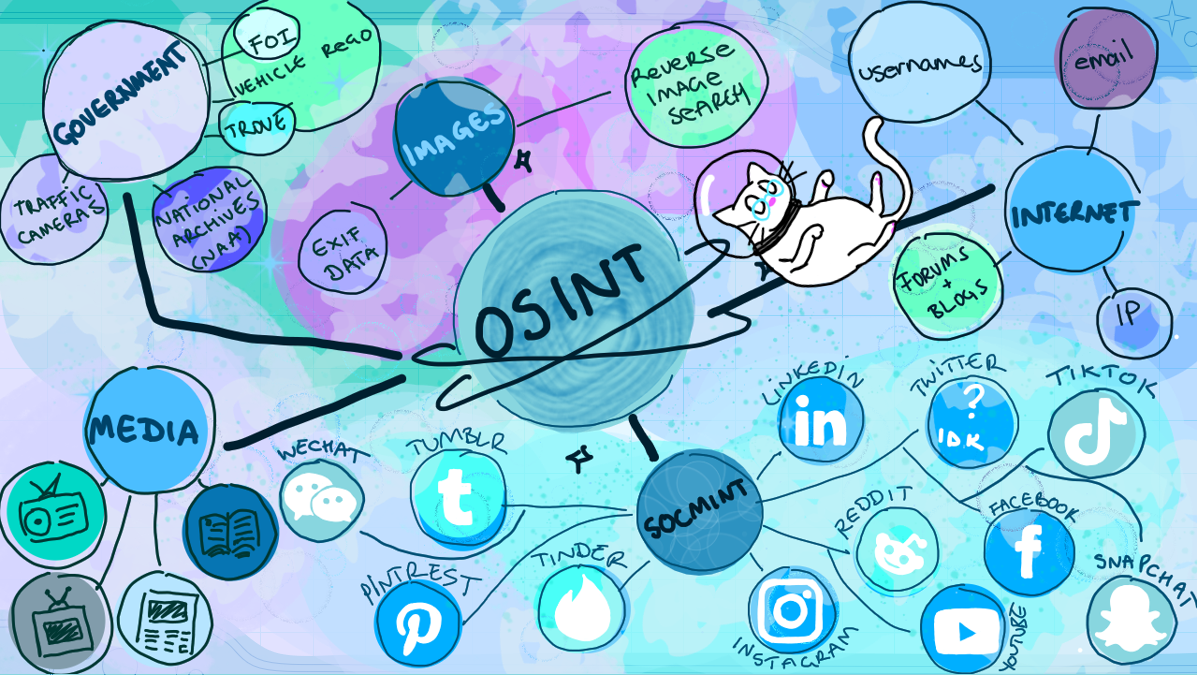

OPEN-SOURCE INTELLIGENCE (OSINT) 4N00BS

Presented by HackerCatz

Presentation

I recently presented something on Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) at work - they were fairly introductory slides and they are by no means an authority on the topic, but I did draw a lot of fun cat pics and I felt they were worth sharing somewhere. I think that’s what the blog is for!

More details and links stored in the Google Slides notes for those who are interested - you should be able to click the “Google Slides” button on the lower right of the embedded slide deck below to get to them.

Published on 21 August 2023.

AI, Automation, Art & Aesthetics

All featured artworks drawn impatiently in MS Paint.

Context

In May this year I was invited to talk on a panel about AI at Scienceworks - for those who are unfamiliar, it’s a museum (or play-space, really) dedicated to science. I spoke alongside Linda McIver, Moojan Asghari and Holly Ransom - a formidable group of women who are absolute experts. We spoke about how AI will impact education, the climate, laws and regulations, data privacy…

One of the audience members posed a difficult question: how did we feel about AI and art?

I fumbled through my response - I’d been avoiding the discomfort I felt every time I saw an AI generated image, undoubtedly trained on unconsenting data.

One one hand…

- I’m excited to see more people generating creative outputs!

- I’m excited to use models to help me generate reference images for my own art!

- I’m thrilled to make ostentatious slide deck animations with minimal effort!

On the other hand… It’s disheartening to think about the artists who have spent years honing their craft and unique styles, only for their data to be stolen from them, and used to effectively replace them - all without credit.

I left the Scienceworks event pensive and apprehensive - I wasn’t ready to confront the elephant in the painter’s room yet.

A few weeks later, I was invited to speak on another panel - specifically because my interests intersect both art and AI. I was flattered - being recognised as an artist is always heartwarming given my paid work is all computers.

I also panicked. I’d really have to face this now.

In this blog post I’ll outline some of my thoughts about art and AI, but don’t expect me to solve any of the problems I identify here. I don’t think I ever will.

Becoming Obsolete

Lamplighters

My favourite book continues to be Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. The novel is saturated with whimsy, from the childlike narration style and illustrations, to the futile and strange characters who inhabit each planet. Chapter XIV is 3 pages long, and visits a planet inhabited by a lamplighter. Over the years, the planet’s day and night cycle has grown increasingly short – at the time we meet the lamplighter, each day is only a minute long, and he laments that he must constantly light and extinguish his lamp.

As a modern reader this is exquisitely silly - imagine committing to such an absurd job! The lamplighting profession has been dead for decades now, and if I was stuck on a planet with the job of switching the lights on and off, I’d certainly have automated myself out of the job by now… or I’d have asked an electronics engineer to help me do it.

Old Treasury Museum

The Old Treasury Museum is currently running an exhibition about these since-obsolete professions, called “Lost Jobs.” It’s there that I learned in Melbourne, “The Metropolitan Gas Company employed 132 lamplighters in 1912. By 1933, there was only one left.”

An interesting theme that threads the exhibition together is the importance of the human beings who performed these roles. Whether it was the cheery impact of a tea lady, the harrowing realities for unwed mothers, or the simple fact that minimum wages were set for the purpose of raising families, the exhibition centres on what can only be described as the human condition.

The exhibition left me wondering whether my job was more parts human or technology, and whether a less human job somehow meant I’d stave off my own obsolescence for longer. I admit, it is a comfortable time in history to have the skills required to program our AI overlords. Some of the most human roles in customer service and creative thinking are looking unstable. For just a few examples I’ve seen in recent months…

- Wendy’s, Google Train Next-Generation Order Taker: an AI Chatbot

- BT to cut 55,000 jobs with up to a fifth replaced by AI

- Dropbox lays off 500 employees, 16% of staff, CEO says due to slowing growth and ‘the era of AI’

- IBM to Pause Hiring for Jobs That AI Could Do

Markets and Marxists

Robots will take all our menial jobs

So let’s talk about being replaced by robots.

With the release of ChatGPT, the average person is not only aware of AI - but they’re playing with it. They’re generating marketing material and editing their photos. They’re replying to emails with personal-tone-adjusted replies. They’re writing blog posts like this one with the help of LLMs to generate ideas. They’re making interesting music, summarising academic articles, generating stronger passwords… Everyone is using AI in a visible, and often well-branded way (think rising household names like Bard, ChatGPT, Adobe FireFly, Bing Chat, and so on.)

Of course, there’s an undercurrent of concern.

- If the robots can do my job, will I stop having a job?

- Will many people stop having jobs?

- If there aren’t enough jobs left in the world, what happens to my income?

- Am I fated to a universal basic income or to perish?

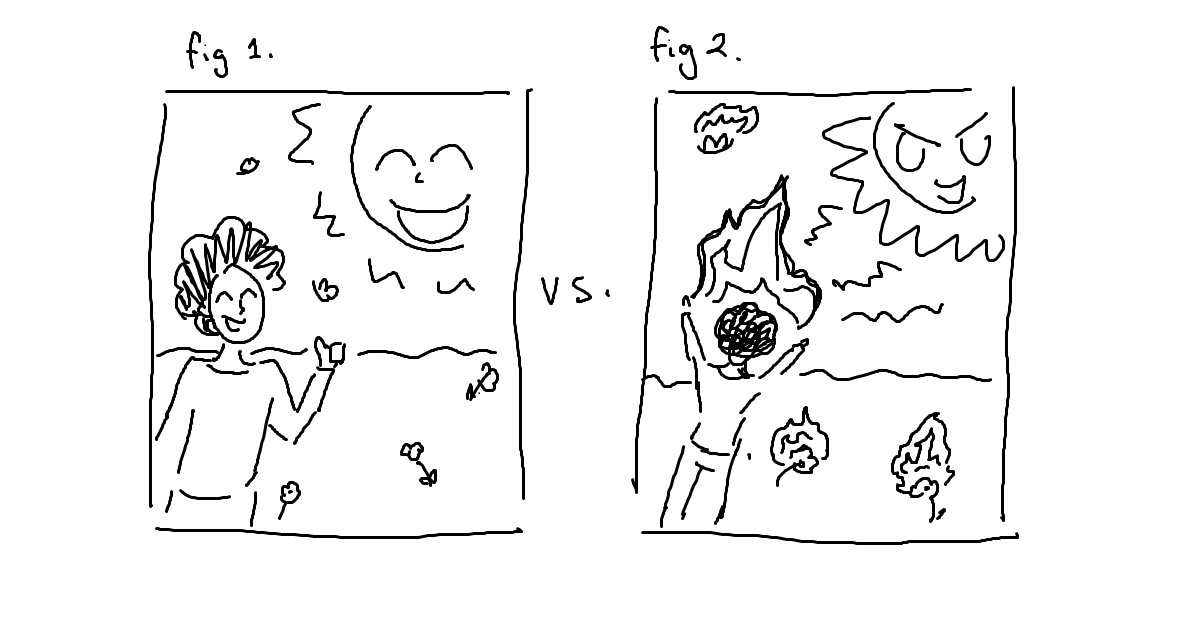

We’re forced to grapple with two possible worlds here.

World One: The utopian version of this thought experiment leads us to believe we’re finally unshackled from the weight of our workloads, liberated by automation to pursue our passions, our relationships, our dreams. Being replaced by AI is an ideal outcome, assuming we can all still drink, eat, and be housed. Maslow’s Hierarchy and all that.

World Two: The version of this thought experiment which is cognizant of the neoliberal profit motive is far less positive. We have all observed how new technology and rising productivity haven’t resulted in increased purchasing power or a drop in working hours for the average person in first world countries. It is hard to believe that the creation of more capital (AI) will generate socialised benefits.

So while being automated out of work sounds like a dream… the reality is that we are afraid of the automated future.

Wait, robots will take our creative and fulfilling jobs too?!

Now, I don’t think most of us walk around terrified of being replaced by robots. We comfort ourselves: “I’ll find a job that the robots can’t do” or “the robots will just do the boring parts of my job anyway.” In some ways, we believe the advance of technology will free up more time for those tasks which are fundamentally human. The spreadsheets belong to the robots, but decorating the stakeholder presentation with cat comics? That belongs to me!

What is “new” with the advent of generative networks (that is, AI that can “generate” things like text or images), is a threat to something we thought was intrinsically human - creativity and the creation of new things. Mike Seymour of University of Sydney summarises the sentiment:

“The problem here seems to be that we thought that creativity, per se, was the last bastion, the line in the sand, that would stop machines from replacing someone’s job … I would argue that that’s just some kind of arbitrary notion that people had that caught the popular imagination”

Artists and the Dismal Science

I’m privileged to be an artist whose artworks are entirely for the fulfilment of my soul, not my bank account. For the class of artists who do depend on their art for income (income which is rightly deserved for creating value, mind you), what does this mean for the viability of their jobs?

To be clear, I don’t think art is a purely economic output - Marx himself once criticised capitalism on this basis, stating that “the dealer in minerals sees only the commercial value but not the beauty and the specific character of the mineral.” However, with the advent of generative AI, we are urged to ask questions like:

- Why pay a photographer for a stock image when a Bing AI can spit one out which has been trained on those photographs?

- Why pay a graphic designer when Adobe Firefly can do it all for me?

- Why pay an artist to design my album cover when I could hack it together with Midjourney?

To compare World One and World Two again here, I’ll define two ways artists make money.

The Corporate Artist: We pay artists to create visually interesting things to create economic value. If a shiny image makes me click on your webpage, then I’m also likely to see your advertising and generate revenue. A glance at popular YouTube thumbnails say everything you need to know about the attention economy.

The Economically Individual Artist: Art which isn’t created for business driven purposes is funded via means like personal commissions, buying merchandise, donating via KoFi… and a lot of what drives this engagement is a belief that what’s being purchased is unique, personal, meaningful. I pay for a portrait of my dog because it’s MY dog. I pay for a print of my favourite artists’ work because it is unique to them. The value of this uniqueness is codified in copyright law and exploited by NFTs.

In World One, we might imagine that artists are unburdened by corporate creations, freed to create whatever it is that they truly love and to build their own businesses.

But in World Two?

The Corporate Artist seems to be wholly threatened by AI, a concept explored well in this article. As someone who still obsesses over Microsoft Office clip art and its artists, a world without human-generated corporate art worries me. Could an AI have generated screen beans?

And the Economically Individual Artist? Well now an AI can work on my dog commission …and in a thousand styles, for free, in less than an hour. My favourite artist’s unique style can now be replicated with some key words, AND I can make them draw ANYTHING I want!

I have always envied professional artists and creatives - I’ve wondered how technically beautiful or ground-breaking my own art would be were I to practise it for 40 hours every week. I wonder what happens to the world when those jobs are taken away.

Photography and Sun Worship

This isn’t the first time a triumph in technology has threatened the creatives of this world - the 19th Century saw massive advances in photography, and with them, threats to the role of artists in society. If a camera can paint the truest possible representation of the world, what use is a technical artist or realist painter? In fact, why do we care so much about art anyway?

The Socratic Machine

It’s the 19th Century. God was dead and science had triumphed, filling the void.

In the Western World of the 19th Century, there was a rabid desire to accurately and precisely capture, record, catalogue, detail and understand the world around us - and cameras promised an unbiased method of capture. The outputs of science and technology were placed above all else, presumed to be superior, accurate, and most useful. We can see the same thing happening with AI now, where people blindly assume the machine generated output is correct, by virtue of being technologically generated.

In the modern day of course, we acknowledge all sorts of human involvement and bias exists in photography and actively exploit these qualities. We’re still collectively learning to identify and acknowledge this bias in machine learning model outputs - Linda covered this really well in a recent blog post.

Charles Baudelaire had some especially scathing remarks about the incredulity of replacing art with photography:

‘Since photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire (they really believe that, the mad fools!), then photography and Art are the same thing.’

And…

‘What man worthy of the name of artist, and what true connoisseur, has ever confused art with industry?’

Baudelaire had not imagined that photography would eventually be recognised as a form of art all its own, entirely distinct from the ravenous scientific purveyors of the time. Where scientists exploited the camera for its infallibility, artists exploited the extremely human characteristics of photography, evoking emotion and exploring new techniques and effects.

If the much-criticised photographer could become an artist, then what can we say of AI?

An Aesthetic Take on AI

The most challenging subject I did in my undergraduate degree was Aesthetics. The readings were brutally obtuse, dragging us unwillingly through the violent, the abject, and the sublime. The subject was one of the only times I’d seen art and beauty taken so seriously, with academic rigour applied at similar levels to what I’d seen in my pure maths subjects. I have a few thoughts about the aesthetic role of AI in recent weeks that I may as well add to this blog post.

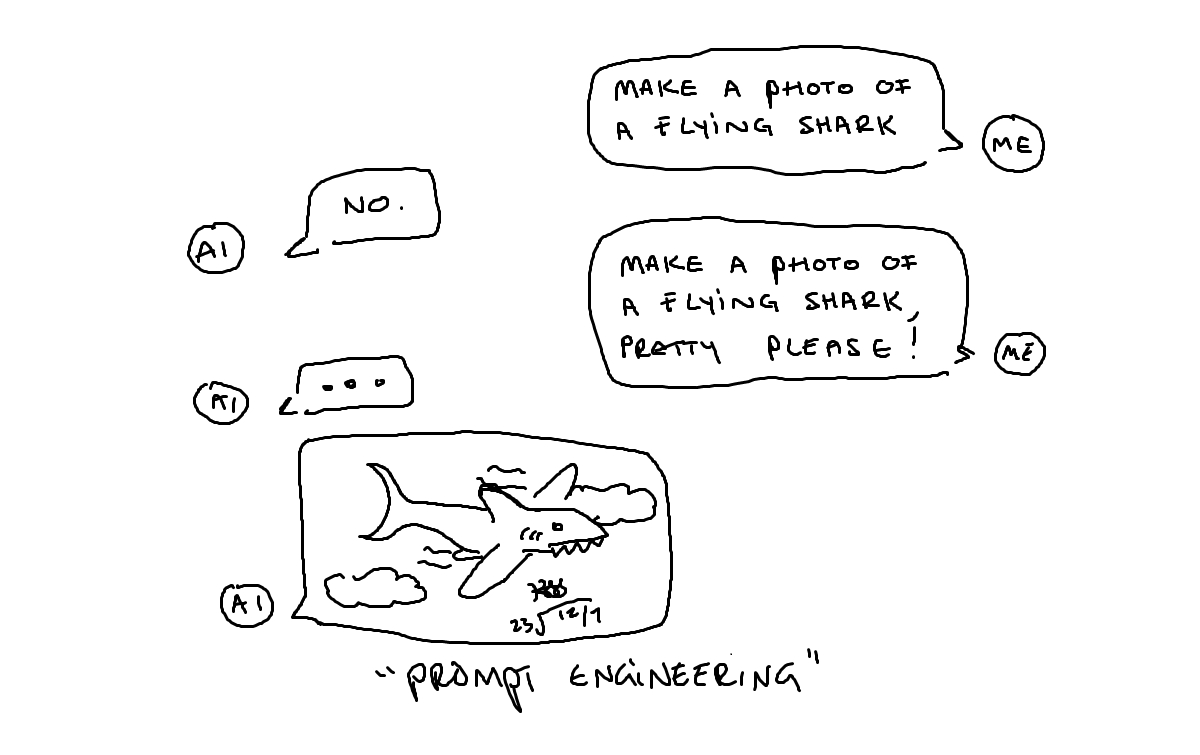

I’d like to propose that prompt engineering constitute a type of art, if you’re using the Nietzschean aesthetic framework. A few definitions…

…prompt engineering?

As many of us have discovered, half the battle with generative AI is crafting a prompt which generates the output we need. Many people have experienced the joy of a chat-bot hallucination, where it confidently asserts that 2+2 really is 7. One method to get around these bizarre results is to provide the chatbot with a worked example of a similar problem, and ask it to explain its answer step-by-step. This is one example of prompt engineering - writing better questions to improve the results generated.

On a side-note, I was recently nerd-sniped by a game which relies entirely on prompt engineering. The goal? Convince a chatbot to give you a secret password. How? Write increasingly clever prompts and exploit the qualities of AI to obtain the password. Given the sheer number of hours myself and my friends spent here, it’s clear to me that prompt engineering is an emerging skillset.

Back to Nietzsche

Right, so prompt engineering is all about writing AI prompts in clever ways. How could that constitute art? Having written a truly absurd amount at this stage, I’ll keep my thoughts here brief.

- Remember, God is dead for Nietzsche (and with that death, comes the death of an objective morality or truth to rely on.)

- Nietzsche was a firm believer that we could never really see the world around us in its truest state - it’s part of why he’s critical of the Socratic man in his writing. There’s a concession that of course we must act as though we can truly see the world for the sake of our own sanity, but there’s always a gap between us and the true state of things.

- If we can’t possibly understand the world around us, AND God is dead, then what is left for us? Well, for Nietzsche…

- “Only as an aesthetic phenomenon is existence and the world eternally justified.”

- Nietzsche is a firm believer that art justifies itself, and that it possesses a unique ability to remind us of how we construct the world around us and can never really see it - art uncovers to us our own self-deception.

- “We possess art, lest we perish of the truth”

- Prompt-engineering could certainly be considered a form of Art under the Nietzschean aesthetic framework - generative AI creates falsehoods, representations of the world around us that appear to us as real.

- Prompt engineers and AI developers remind us we are being deceived, that the creativity of the models are just piles of mathematics.

And so, interestingly, AI falls into the same space photography once did - all at once threatening the livelihoods of artists, conjuring debates about art vs science, and fitting neatly into the Nietzschean Aesthetic framework.

Wrapping up…

These are all the thoughts swirling around in my head when it comes to AI and art. I’m asking myself what the economic future of artists looks like, and whether it’s capricious to declare AI exempt from the status of “art” itself. You’ll notice I’ve left many things unresolved and I’m not sure I will ever resolve them. You’ll also notice I refrained from ranting and raving about the Apollonian and Dionysian despite having some good opportunities to do so - you’re welcome.

Music

And as a final congratulations for sitting through what has essentially been a ramble-post, here are some of my favourite tech-themed-beats.

- Youtube Playlist: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7SrOiqvqNyZvQ3lD79nYZo_7pix0F7m6

- Spotify Playlist: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7KmNAwGfIv9HuSWFGZEHYq?si=613d2526af2f4e91

Published on 12 July 2023.

Practical Fashion and Rationality in Technology

A self-indulgent reflection on what it means to be eccentrically dressed as a technologist.

The Law of Practicality

When you work with computers (or mathematics, or any other logic-dominated thing) there’s a sense that the whole world can be reduced to a few sets of rules and principles. Clothing isn’t exempt. “I wear cargo pants to carry my stuff. I wear a hoodie because it’s clean and warm. I wear sneakers to carry my body around.” The Standard Rationalist uniform.

The Law of Practicality governs technologists’ wardrobes, more interested in climbing through wiring closets and staying warm than in impressing others. It’s the essence of the Steve Jobs turtleneck. It’s an impressive commitment to rationality and functionality that permeates the field.

We’ve been making fun of technologists’ “professional” outfits for a long time - only last week I saw jokes about the tech uniform in a Slack channel. Another channel was advocating that if comfy shirts and jeans worked for men, they were fine for women too. Pure, pragmatic rebellion.

Despite the freedom to wear non-traditional clothing to the office, I have seen very few people step outside of the shirts-shorts-sneakers style. Amidst so many unconventional individuals, I still feel especially strange as a gothic gal.

I’ve met one other tech-person with a facial piercing. I’ve met one stylish man with a brilliant black coat and functional gas mask. I have recently joined forces with other velvet jacket wearers. These folks are few and far between, and I can be quoted saying that we need more goths in tech.

Delectably Impractical

I feel out of place because I am a die-hard impracticalist when it comes to fashion. I love looking through Vogue for the latest piece of couture, completely unwearable on the metro trains I inhabit. I love hunting through op shops for shoulder-padded frilly things.

This week, I tuned into a Mina Le video essay about impractical shoes. She explores shoes across cultures and historic periods, considering beautiful beading, platforms which require assistance to walk in, and the materials used to construct these art pieces. Go watch it, it’s fascinating - and it’s what prompted this blog post.

I have a personal history with impractical clothes, owning a pair of platform boots before I was 10.

Throughout highschool I insisted on wearing a top hat everywhere. I made a spare one out of determination, school worksheets, duct tape, and a reel of shark patterned fabric, lovingly coveted in a sewing class. My later school years were punctuated by frequent corset appearances, worn from dawn to dusk.

My wardrobe has only spiraled from there. My favorite coats are decked out with lace and pirate sleeves. My favorite shirts are ruffled and strange. I shop Halloween sales for regular wardrobe items.

I proudly recall wearing my “standard” winter coat to work one day, and a colleague remarking - “wow - there’s a lot going on there.”

Spooking the Squares

There’s an identity crisis attached to being impractical in a logic-governed world.

Before university, I had accepted that I was a tortured creative soul, writing poetry and making art of horrible things. I was interested in Renaissance history, Mark Rothko and Bright Eyes lyrics. I submitted assignments by typewriter.

At university, my philosophy classes were opportunities to push the absurdity of my last outfit one step further. Those classes were full of other impracticalists… but my math classes made me shy.

I tried to convince myself pure math was all about eccentric creatives too. I wrote essays about beauty in mathematics and mathematics in poetry. I was desperate to find the incoherent and chaotic creatives in these caves of clarity.

In my last 2 years of university, I started wearing extremely girly outfits to my math classes, rebelling against the utilitarian look surrounding me. It helped me cope with imposter syndrome - people weren’t avoiding me because I was stupid, but because all the boys were scared of my hot pink boots. I ran experiments with myself, showing up to one class overdressed and the other in the Standard Rationalist, noting I made friends faster when I was less feminine.

By the time I finished university I had only become more defiantly strange. I started working in tech.

The Mosquito People

I recall having a conversation with a coworker about “professional” clothing. He surmised that that we work with eccentrics (AKA researchers), thus looking eccentric is a good way to break the ice. Being weird on the outside was a good signal for people who were weird on the inside. I didn’t quite believe him following my university experience. It was one thing to wear a dorky chemistry shirt and quite another to come to work as a pirate.

But he was right.

Shortly after this chat, I finished reading Dracula. As a reward, I bought myself a shirt emblazoned with “DRINK MORE BLOOD”. I saw no reason to not wear it to work. On one occassion while wearing this provocative shirt, I found a colleague in the foyer chatting to some researchers. They cracked up laughing.

“We let mosquitoes bite us as part of our research. Drink more blood!!!”

I’d never been so proud to be so strange. They were excited to be strange with me. I learned a lot about the process of mosquito research and got myself an invite to the lab, should I ever be interested.

Carrying the torch

So while I still feel “out-of-place” in my excessive outfits, I relish working where The Law of Practical fashion reigns. Where else could I wear a sequin tailcoat or cat ears without any kerfuffle? And what on this earth could be better than the freedom to be bizarre and meet a tank full of mosquitos? Good luck answering that one, dear reader.

The Palmer Penguins Dataset

A brief blog about my new favourite toy dataset

Meeting The Iris Dataset

I started my Python journey in 2017, using Jupyter to learn the usual scientific computing suspects like matplotlib, pandas, scipy and numpy. I remember the day I found Seaborn - I was thrilled by the array of colourmaps and the easy-to-make-pretty graphs. I quickly made coloured copies of a Spiderman image.

In 2018 as I veered into machine learning territory, I got myself a CSV copy of the Iris Dataset. If you haven’t met it before, it is ubiquitous in ML - it’s a nice clean dataset with:

- 150 photos of Iris flowers,

- 4 captured variables (petal lengths etc.)

- 3 species of Iris flowers.

The goal is to build a model to classify images by species. The dataset’s popularity is largely driven by its small size, easy access and data-cleanliness.

More importantly for this post, with a few simple plots you can start to see which variables might indicate a difference in species and see some tidy clustering. Before you know it, you’re learning about data visualisation and multivariable classification methods and annoying your friends with your newfound knowledge. Welcome to ML.

Fash-on

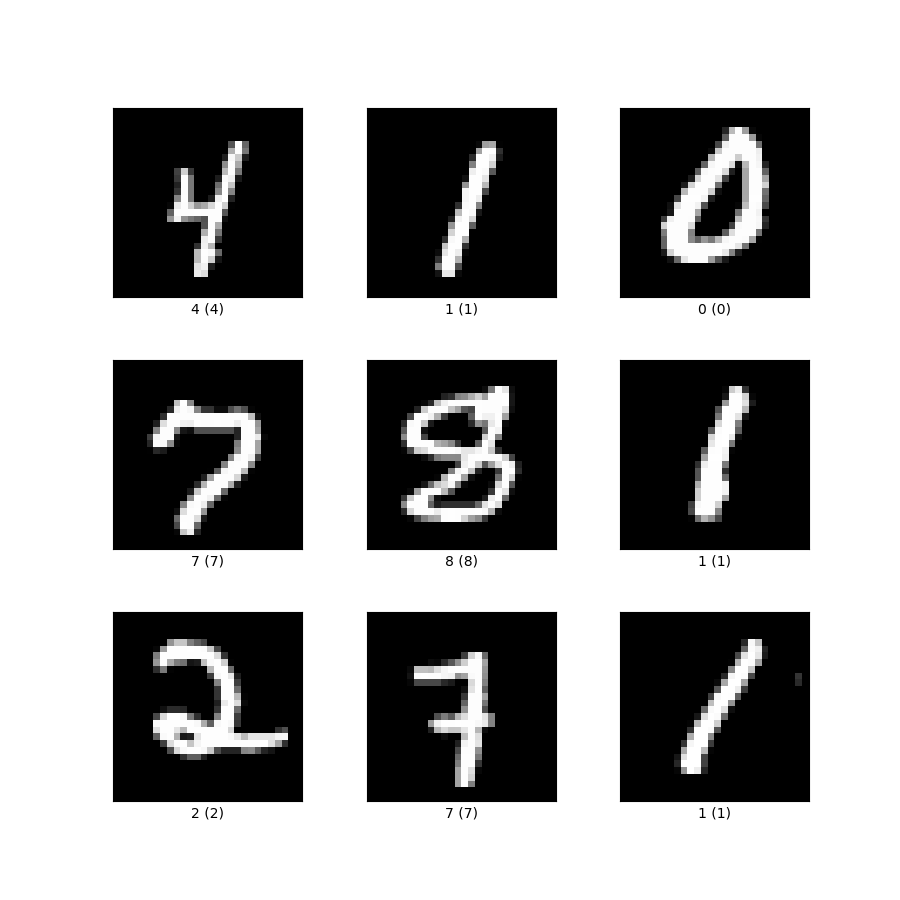

Before long I was exposed to all the standard datsets - CIFAR-10, the Boston Housing Dataset, the Stanford Natural Language Inference Corpus… and MNIST, a datset consisting of handwritten numbers from 0-9.

Your task? Train an algorithm to recognise the numbers correctly. This one is fun because while only a botanist might see the value of flower classification, non-scientists can see the intrigue in being able to read handwriting with computers.

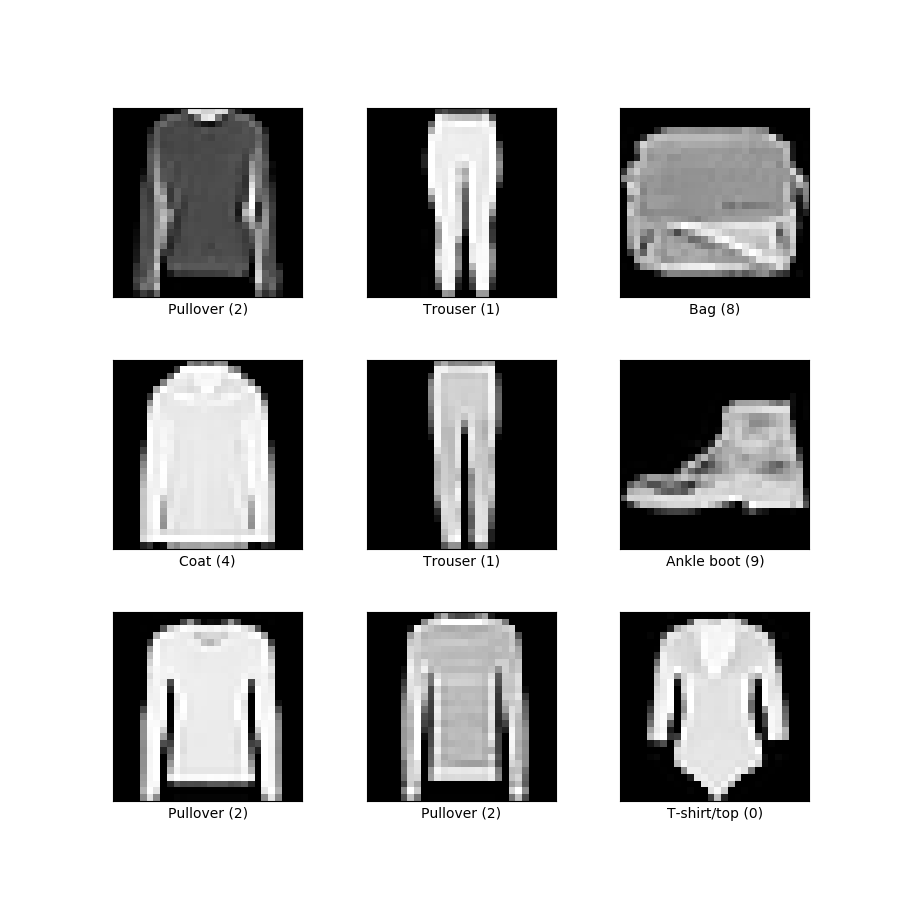

One day while reading a paper, I found something called Fashion-MNIST - instead of handwritten digits, we had a dataset with photos of different categories of clothes - jackets, boots, skirts, etc. It was touted as the new MNIST - slightly larger and slightly more difficult, to match the rapidly advancing capabilities of ML.

I was thrilled by the idea of an “upgraded” datset consisting entirely of something as random as clothing. I felt like a real academic, discovering new data in papers. I was so fond of this cool new dataset that I used it to implemenmt encrypted logistic regression in C++. I delighted in introducing the dataset in the paper I worked on.

Into the woods

Since then, I’ve met a lot of interesting (mostly image) datasets - everything from chest x-rays and skin lesions, to mammoths like Imagenet and COCO, and even some real world reference data.

Despite this exposure, I’ve always gone back to Iris when I’m working with something new. Testing new hardware? Building a new Python environment? Just want to make some pretty graphs? Well, Iris is built into a bunch of Python libraries, it’s fast to load, and it feels like a book I’ve read 100 times, meaning I can focus on whatever problem I’m solving instead of on the peculiarities of the data.

And so last week when I was asked to mock up some pretty plots, I figured I’d use ye-olde-iris to get the job done. I searched for something like “iris pairplot seaborn” to jog my memory. Within the search results was a link titled IRIS ALTERNATIVE - PALMER PENGUINS.

Introducing the Palmer Penguins.

All the excitement I felt upon finding the Fashion-MNIST was reborn in that moment. An alternative to Iris? WITH PENGUINS? I was sold.

The Palmer Penguins dataset has 300+ penguin samples captured from the Palmer Archipelago. It’s almost a one-for-one stand in for Iris, coming with some extra categorical data (species, island, and sex.). This meant I was in very familiar territory, with some added intrigue.

I immediately set about to producing my charts with this shiny new data. I quickly learned that heavier penguins had longer flippers. Of course, being very far removed from penguin research, I hypothesised that maybe bigger flippers = faster swimming = more fish, or maybe bigger penguins are just bigger all over, or maybe fatter penguins have the resources needed to grow longer flippers, or…

Brilliant. I was thinking about chunky penguins instead of flower petals - what’s not to love?

And so this blog post is a short callout to the Palmer Penguin dataset and the joy it brought me. I can only wish for fashion-penguins on the horizon…

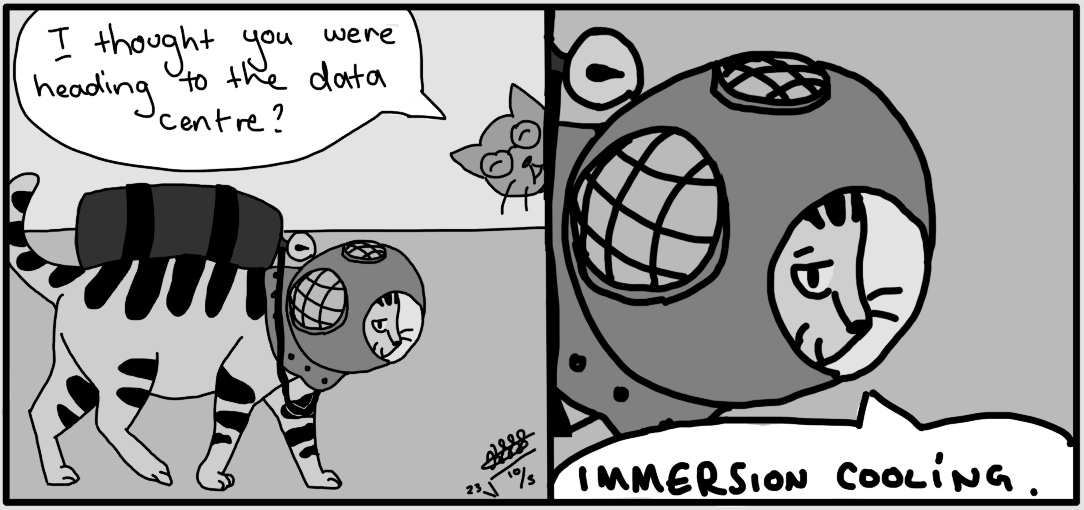

Immersion Cooling

Scuba cats in the immersion-cooled data centre

Published on 10 March 2023.

Women in Tech Talk for International Women's Day

A blog version of a talk I gave about the history of women in tech for IWD 2023

What’s this post?

I was invited to talk to a group of high-school students for International Women’s Day at Casey Tech School in 2023. I invite you to check out the Google Slides I presented for this event if you’re interested, but all content will be covered below in a similar format.

Cracking the Code: Innovation for a Gender Equal Future

“Humans are allergic to change. They love to say, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’ I try to fight that. That’s why I have a clock on my wall that runs counter-clockwise.”

Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, Computer Pioneer

What is International Women’s Day?

International Women’s Day (IWD) falls on March 8th in the United Nations (UN) calendar. The day is committed to advancing the outcomes of women across a variety of challenges, including but not limited to:

- Economic participation,

- Academic participation,

- Reproductive rights,

- Domestic violence and violence against women,

- Equality at work and at home.

The 2023 theme is “Cracking the Code, Innovation for a Gender equal Future”, focussing on how we use STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics) to advance women’s outcomes, and how we bridge the digital gap for women. For example, women in low and middle income countries are on average 18% less likely to have a smartphone than men, and 7% less likely to have a mobile compared to men.

Intersectionality

It should be noted that this blog will focus on women in STEM in the U.S., U.K., and Australia, but it doesn’t at all diminish the experiences of other marginalised groups in tech, including:

- People of colour,

- People for whom English is a second, third or tenth language,

- Gender diverse and gender non-conforming folks,

- People with disabilities, chronic illnesses, or caring responsibilities,

- First Nations peoples,

- People from low-socioeconomic backgrounds,

- Members of the queer and LQBTQIA+ community,

- And others!

Many of the challenges faced by women are the same or amplified for people across these intersectional groups, and diversity, equity and inclusion efforts need to address them all.

I’d also comment that many of the challenges women face within STEM extend beyond STEM.

Stats & Facts

So where are the gaps for women? There’s a billion horrifying statistics you can look at, but here are a few that jumped out to me as interesting.

- Globally, women make up just 19.9% of science and engineering professionals - less than 1/5th!

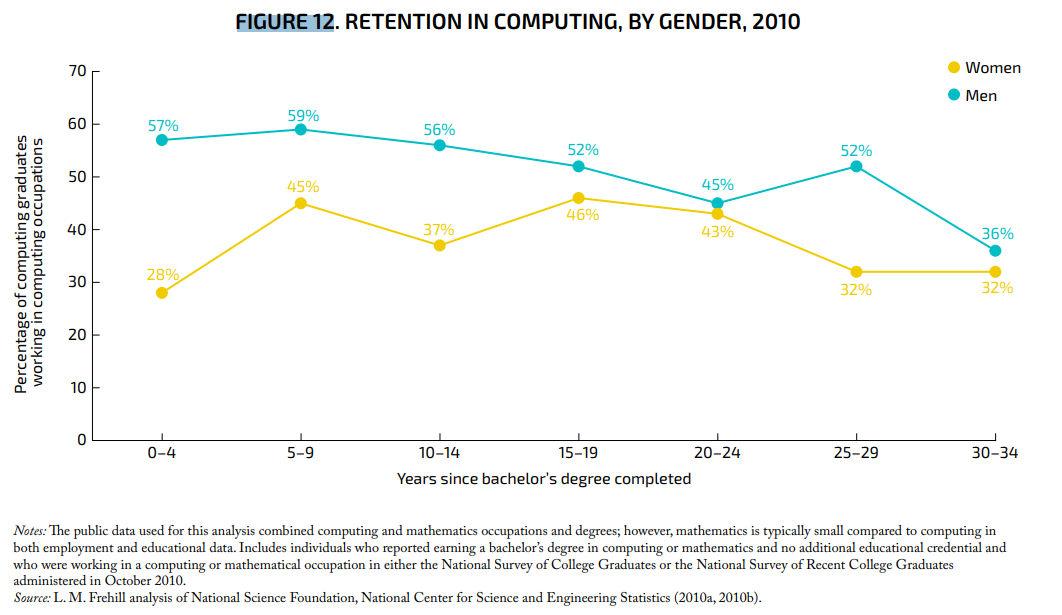

- In the U.S., only 28% of women with computing degrees reported working in a computing job a few years after graduating, compared to 57% of men.

- After about 12 years, 50% of women employed in STEM had exited to other fields, compared to 20% of women in non-STEM fields. A majority of these women are from engineering and computing domains.

- 33.9% of staff at Google globally are women.

- 37.5% of staff at Facebook globally are women. Of the technical staff, women represent only 24.8%.

- According to a 2019 global report, women received 54% of all degrees; the share of humanities, arts and social sciences degrees undertaken by women was 54%, while STEM was undertaken by a share of only 30% women.

These are some sobering statistics - but we’re getting better, right? There’s a variety of encouraging programs for women in STEM nowadays!

Progress is inevitable

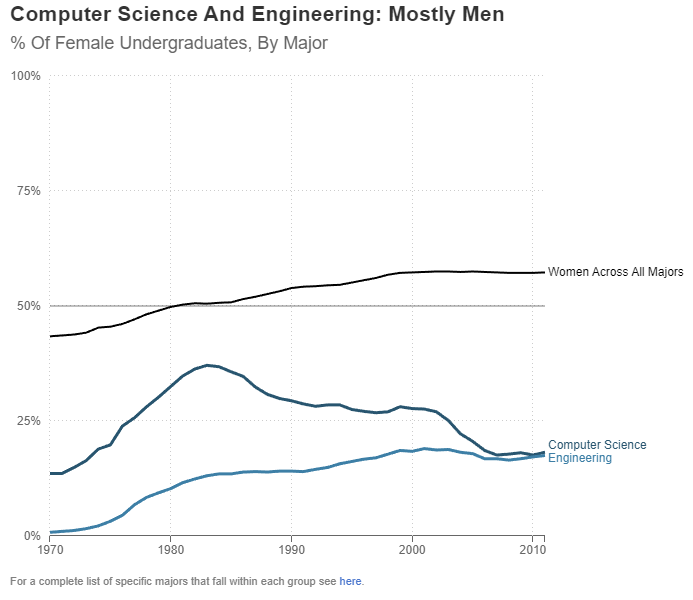

In my philosophy classes at university, it seemed a given that contemporary societies were more advanced and progress was inevitable. Unfortunately, this simply isn’t always the case - while women’s participation in STEM subjects and other male dominated fields has increased over time, computational and engineering degrees are left in the lurch. More women graduated with computing degrees in the 1980s than they do today!

In the United States in 1984, computer science grads were composed of 37% women; in 2018, that number was less than 20%.

Aussie stats aren’t any better - women make up just 1/5th of technology graduates. Ouch.

Herstory

“Wait, so women were once more involved in tech?” I hear you exclaim - I know, I know. Let’s take a walk through the past and see how we got here.

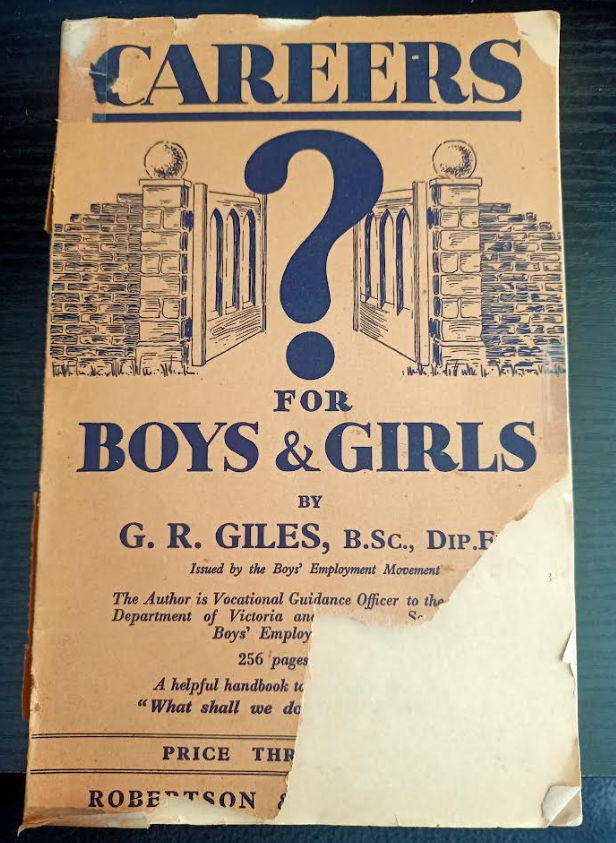

Careers for Boys and Girls - Women in STEM in 1930s Australia

I picked up this lovely book at an op-shop a few years ago!

“Careers for Boys and Girls”

By G.R. Giles, B.Sc., Dip. Ed.

Vocational Guidance Officer, Education Department, Victoria and

Hon. Secretary, Boys’ Employment Movement

1936

It details the variety of careers available in Victoria, Australia in 1936, and provides advice on training and education, writing cover letters, and what the workforce is like. Many of the jobs within have special sections or advice for women entering the workforce. I’ve tried to focus on the STEM portions of the book here, though there is a gnarly section detailing the different pay grades for male and female teachers which I must regrettably omit as a result.

I’ve also tried to minimise images and transcribe as much as possible - for photos of these sections, refer to the Google Slide deck.

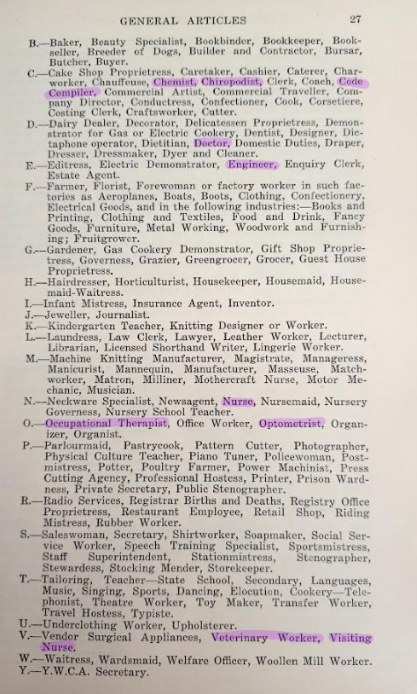

Careers for Girls

This special section is titled “Careers for Girls” - there are no STEM careers listed under the letter A on the overleaf, so I’ve highlighted the STEM careers available from B-Z here:

Under health and life sciences, we have:

- Chiropodist,

- Doctor,

- Nurse,

- Veterinary worker,

- Visiting nurse,

- Occupational therapist,

- Optometrist.

Let’s zoom into some of the listings for these professions later in the text.

Opportunities for women - doctors

Throughout the course there is no sex discrimination, women being admitted to the lectures and hospital work on equality with men. An increasing number of women is taking up this profession, and, with the decay of the prejudice against women doctors, there are opportunities for them in many fields.

Oh good, discrimination against female doctors was trending down!

Openings for women - optometry

It is estimated that in normal years there should be vacancies for about 50 boys and 10 girls annually.

[…]

During the last few years an increasing number of women have entered the profession, which appeals to girls. Conditions of training apply equally to men and women; the number of openings for women in this field is, however, limited.

Oh, okay, arbitrary hiring limits. Sure…

Openings for women - Veterinary Surgery

In 1934, there were almost 100 students in this course at the Sydney University, including 6 women. The opportunity for women practitioners in veterinary surgery is thought to lie in the treatment of the smaller animals, rather than in general country practice, where prejudice and certain practical difficulties may have to be encountered.

[…]

It is not easy to indicate the emoluments for women, in view of the pioneer stage of the profession, as far as they are concerned.

We turned this one around! Interestingly, in Australia in 2016, 80% of veterinary science graduates and 60% of practitioners in Australia were female.

Moving out of the life sciences, we also see some other STEM careers highlighted for women - namely:

- Chemistry,

- Engineering,

- Code compiler?!

Zooming into these professions…

Opportunities for Women - Chemistry

Women are admitted on an equality with men to the professional courses of training, but openings for women in this field are usually restricted to laboratory work, for which they are particularly fitted.

…what is that supposed to mean???

Engineering

Make no mistake - engineering was for men. The text always refers to the young engineer with male pronouns and it doesn’t have a cute little “opportunities for women” section like other fields do.

It does have a section for factory work where women are subject to some unique rules:

- “A child is a boy under the age of 14 years, or a girl under the age of 15.”

- “No female of any age shall be employed in any lead process.”

- “No girl under 18 may be employed in melting or annealing glass.”

- “No girl under 16 may be employed in the making or finishing of bricks […] or in salt works.”

- “No male under the age of 18, and no female of any age, may be employed in wet spinning unless sufficient means for the protection of workers is provided.”

- “No girl under the age of 18 years is permitted to carry or lift a weight over 25lbs.”

Code compilers

Wait, compilers didn’t even exist in 1936!

After a slew of googling, I’ve come to the conclusion this was likely a clerical job around coding paperwork properly. Women must have been our earliest manual database administrators. If you know more about what this could be referring to, or have better Google-Fu than me, please let me know.

So we’ve had a look at the …long list of STEM careers available to women in the 1930s in Australia. Let’s zoom ahead to the 1940s and 1950s and see how women started to dominate jobs as actual code compilers.

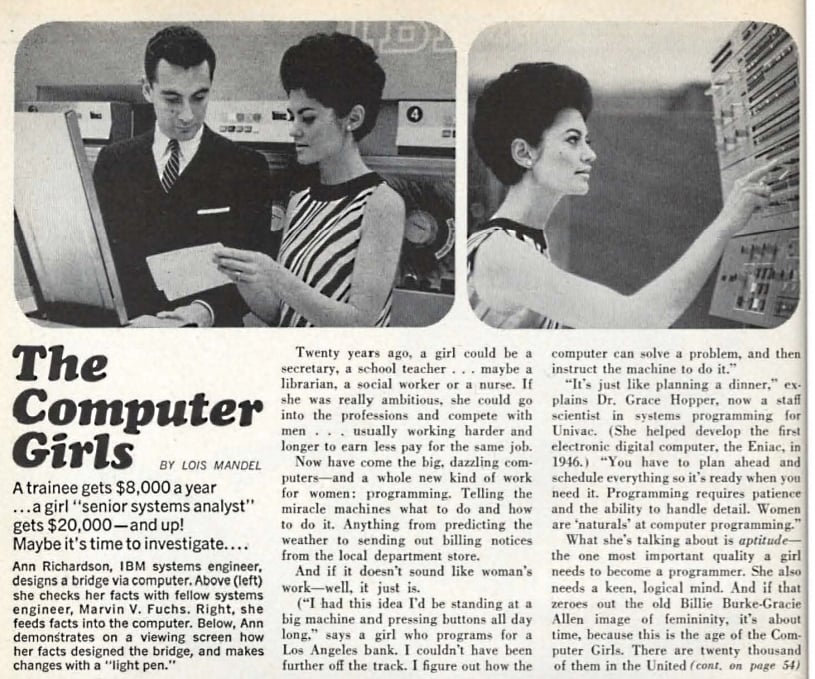

The Computer Girls

A 1967 Cosmopolitan Magazine explains how women are ideal for the world of computing.

Twenty years ago a girl could be a secretary, a school teacher . . . maybe even a librarian, a social worker, or a nurse. If she was really ambitious, she could go into the professions and compete with men, usually working harder and longer to earn less pay for the same jobs.

[…]

And if it doesn’t sounds like woman’s work - well, it just is.

[…]

It’s just like planning a dinner,” explains Dr. Grace Hopper […] “ You have to plan ahead and schedule everything so it’s ready when you need it. Programming requires patience and the ability to handle detail. Women are ‘naturals’ at computer programming.”

Similarly, a 1963 edition of Datamation magazine wrote that “women have greater patience than men and are better at details, two prerequisites for the allegedly successful programmer.” and that “women are less aggressive and more content in one position.”

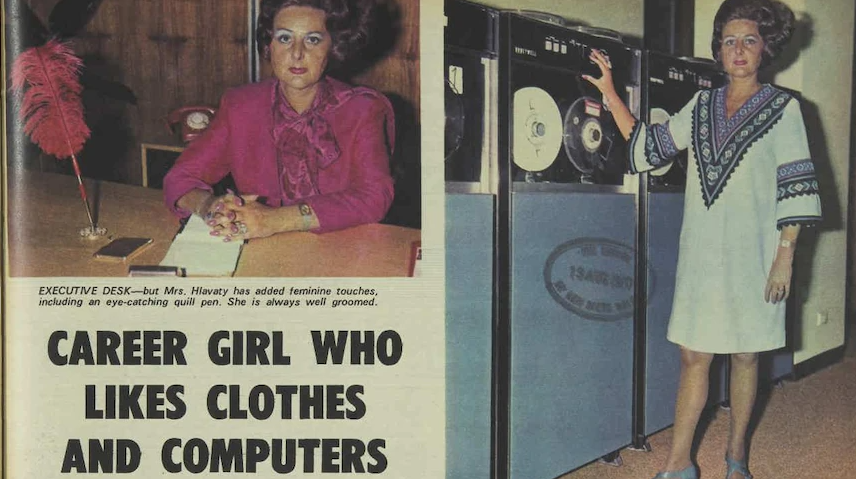

And don’t be fooled into thinking the phenomenon was limited to the U.S. and U.K. - Australia had its own computer women, many working in astronomy. I highly encourage you go and read this ABC Article titled The hidden stories of Australia’s first women working in computing. The article features this wonderful image of Lee Hlavaty from the 26th August 1970 Women’s Weekly issue. I know the 1970s is skipping ahead, but it is too good to not share here:

Anyway, back to the 40s and 50s.

The first programmable electronic computer (ENIAC, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator) was built by men but programmed by a majority of women. In fact, six of the first programmers included:

- Kay McNulty

- Ruth Lichterman

- Jean Jennings

- Betty Snyder

- Marlyn Wescoff

- Fraces Bilas.

This wasn’t out of the ordinary - following WWII, in the 1950s women made up 30 to 50 per cent of programmers!

Why computing is women’s work

Now hold your horses - programmers of this time weren’t highly paid and respected intellectuals - these women were viewed as clerical staff, aligned with typists or stenographers. The lucrative and respected work was in the man’s work of building the hardware (remember our engineering section from earlier?)

The women in these roles (and earlier arithmetic roles) were referred to as “computers”, and in the 1960s IBM UK even measured their computing outputs in “girl hours”.

This excerpt from a Guardian article with quotes from Marie Hicks says it better than I can:

“Computers were expensive and using women to advertise them gave the appearance to managers that jobs involving computers are easy and can be done with a cheap labour force,” explains technology historian Marie Hicks. They might have been on a typist’s salary, but women like the one who appears alongside Susie and Sadie were not typists – they were skilled computer programmers, minus the prestige or pay the modern equivalent might command.

[…]

Managers perceived women to be ideal for the computing industry because they didn’t think they needed to be offered any sort of career ladder, explains Hicks. “Instead the expectation was that a woman’s career would be kept short because of marriage and children – which meant a workforce that didn’t get frustrated or demand promotions and higher wages.”

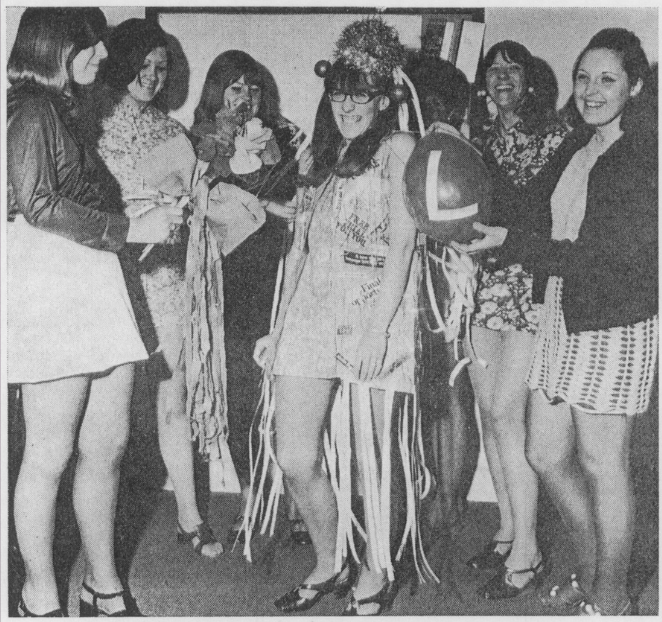

Oh. Right. So women dominated tech precisely because they could be exploited for cheaper labour, and then forgotten when they got married, had children, and inevitably retired. This image of a young lady decked out in computer tape at a retirement party is relevant here:

This super early retirement was extremely common, with laws prohibiting pregnant women from working in many countries. As an example, here in Australia, married women weren’t allowed to work in the public service once they were married, until the marriage bar was raised in 1966. The initial attempt to remove the marriage bar failed, citing reasons of men being too tired to work effectively as they picked up more domestic labour.

What has 16 legs, eight waggly tongues, and costs you at least 40k a year?

Moving through the 1960s, the importance of computer programming became obvious. With the additional respect the field wielded, men began joining the workforce at higher payrates and with promises of career progression. Alongside this increase in respect for computing came the legitimisation of the field with stronger higher education requirements, the formation of professional associations, and the expectation that computing staff would want to climb the career ladder - something women were exempt from.

Historian Nathan Ensmenger, author of “The Computer Boys Take Over”, puts it succinctly:

An activity originally intended to be performed by low-status, clerical – and more often than not, female – computer programming was gradually and deliberately transformed into a high-status, scientific, and masculine discipline.

As part of this legitimisation of the field came career aptitude tests - the System Development Corporation (SDC) had two psychologists, William Cannon and Dallis Perry, create a vocational interest scale. They interviewed 1400 engineers (1200 of which were men) to generate the test. As you might imagine, women didn’t perform especially well on this assessment.

The main finding was that programmers shared a strong “disinterest in people”. Oof, am I really that much of a misanthrope?

A Wall Street Journal article highlights the impact this status change had on the expert women already working in the field:

Memos from the U.K.’s government archives reveal that, in 1959, an unnamed British female computer programmer was given an assignment to train two men.

The memos said the woman had “a good brain and a special flair” for working with computers. Nevertheless, a year later the men became her managers. Since she was a different class of government worker, she had no chance of ever rising to their pay grade.

I know several modern day women in tech would scoff at this historic memo, citing that nothing had really changed since then. I’m sure we could find an equivalent Twitter story.

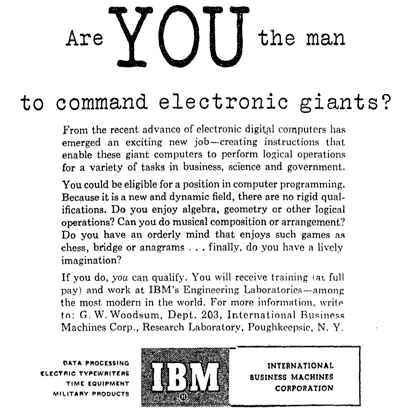

Are YOU the man to command electronic giants?

In 1968 Richard Brandon summarises the average programmer into a stereotype that the modern day audience can completely understand. As recorded in the 1969 ACM National Conference Proceedings:

…the personality traits of the average programmer almost universally reflect certain negative characteristics. The average programmer is excessively independent-sometimes to the point of mild paranoia.

He is often egocentric, slightly neurotic, and he borders upon a limited schizophrenia. The incidence of beards, sandals, and other symptoms of rugged individualism or nonconformity are notably greater among this demographic group. Stories about programmers and the attitudes and peculiarities are legion, and do not bear repeating here.

Richard goes on to explain that these negative traits are directly correlated to aptitude tests singling out the most logical individuals. He comments:

Many people with the logical aptitude to pass numeric or spatial relations tests do not have the basic ability to become part of an effective and productive programming team.

How can you tell if a programmer is extroverted?

They look at your shoes instead of their own. (Badum-Tss!)

Despite these changes, we saw increasing amounts of women doing computing degrees until the mid-80s. And so the mystery remains: what happened in the 80s that was so much worse than beard-growing, sandal-having, people-hating personalities?

What happened in the 1980s?

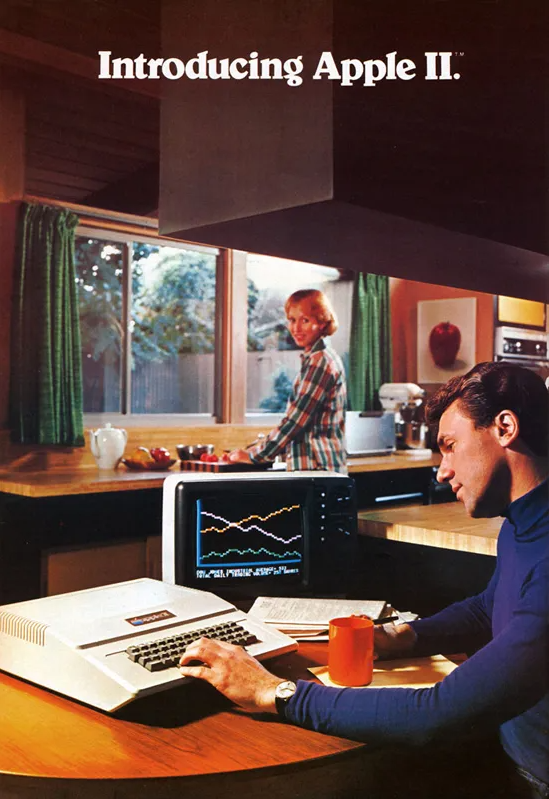

In 1981, IBM launches the personal computer, and shortly thereafter Apple releases the Macintosh - suddenly, people have access to computers in the home!

Marketing in the era is often aimed at boys and men, showcasing these PCs as toys or hobby machines, aligned with the masculine arcade culture of the period. Jane Margolis did a study in the 1990s which showed that families were more likely to buy computers for their boys, even if the girls were interested in them.

Prior to the release of the PC, computer science students usually started from the position of having no experience with computers. Suddenly, some of the students had prior knowledge - and most of them were boys. I have to wonder how many young boys today are building their own PCs compared to girls.

Patricia Ordóñez recounts her experience as a woman heading into computer science in the 80s, realising she was already “behind” her male colleagues.

The professor stopped and looked at me and said, ‘You should know that by now,’ she recalls. “And I thought ‘I am never going to excel.’

Patricia eventually moved to majoring in foreign languages.

There are many theories as to the downturn in women in tech which occured in the 80s, but many of them turn to these massive cultural (Revenge of the Nerds, anyone?) and academic changes, transforming computing into a very male space.

Back to the theme - ✨Innovations✨

A lot of the studies have focused on fixing women—fixing their confidence, fixing their interests. We did not find that any of those factors influenced women engineers’ persistence decisions at all, which is why we are saying we really need to be focusing on the environment.

Nadya A. Fouad

Right - so we’ve seen that there aren’t enough women in tech, that the numbers are actually down compared to the 50s and 60s, and started to understand why women may not have pursued these degrees and careers. But the theme of IWD is all about innovation to address these issues - we can fix this with more technology, right?

WRONG.

I did a lot of reading on this topic before giving this talk - and I simply don’t believe the problem here is the lack of technology, or lack of studies on women’s participation and retention in STEM, at least not in developed nations. Let me tell you about two innovations to demonstrate my point.

The Work-From-Home women - U.K.

In 1960s England as women were pushed out of technology, Stephanie Shirley dared to be different, starting her own company: Freelance Programmers. In short, she gathered a workforce of mostly women who worked from home - a rarity in this time. She also pioneered the ability for career-re-entry and job sharing arrangements, offering an attractive workplace for other women like her. 297 out of her first 300 staff were women.

Much of the programming of this era was done on paper, with limited need for actual computer time, so women were able to work from home and balance their domestic duties and childcare. After an initially challenging sell, Shirley started going as “Steve” on business communications, a move which worked especially well for her.

The Work-From-Home Women - U.S.

Similarly, across the pond Elsie Shutt started Computations Incorporated in 1957, as she was unable to remain employed by Honeywell after falling pregnant. She failed to negotiate working part-time or subcontracting, and so incorporated with a few of her colleagues in a similar position.

Elsie actively hired women who were pregnant or had caring responsibilities, and even had a training program for women who wanted to get involved with computing while they worked from home, getting them job-ready for once their children were grown up.

Conclusion

And so what do I take from those two examples?

Smart women, scientists, researchers, technologists, have known the solutions to many of the drivers of inequity for a long time. There exists swathes of papers detailing issues including:

- The unequal domestic household burden women bear,

- The confidence gap which appears in girls in maths classes as early as grade 4,

- The fact that women excelling in masculine fields are perceived as either competent or warm, but rarely both,

- The inequitable funding for women’s research and enterprise,

- The benefits of work from home and other flexible working practices which women implemented IN THE 1960s! (Facebook’s diversity report, linked earlier, highlights most of its remote roles were filled by women.)

- The many embedded biases in AI systems…

And the list goes on.

Technology identified the problems. A fundamentally inequitable system persisted them.

Published on 06 March 2023.

ATSE ELEVATE "Boosting women in STEM" program launch speech

A speech I gave at Parliament House in November 2022 about women in STEM leadership.

Background

In November 2022 I was invited to Parliament House as one of the inaugural recipients of the ATSE ELEVATE leadership scholarship, and given a few minutes to respond to a big question. I chose to speak about what it’s like to be a woman in STEM.

That particular talk was very well received and quite important to me. I’ve transcribed it below.

The Speech

Dr Marguerite Evans-Galea AM:

“As you continue your leadership journey, how will Elevate help you increase your influence and impact?”

Kiowa Scott-Hurley:

“One day, I am going to apply for a senior leadership role.

I will have the academic qualifications.

I will have the years of experience.

I will have built the network, done every leadership course, aced the interview…

And I won’t get the job.

I was in my second year of university when I learned about the STEM sieve. Women come into the top of the sieve, and we catch a handful with biology, chemistry, and psychology. A few women filter through to engineering. Fewer still land in maths. Sometimes tech gets the scraps.

Every layer of the sieve requires women to be succulents - to withstand hostile environments and to adapt rapidly. Here at the bottom of the sieve in tech, I feel like a cactus in the Antarctic. I do not belong here.

I also started my first tech job in my second year of university. In the interview, I was told I wouldn’t work with many women. My interviewer knew about the sieve, and he knew it wasn’t a good excuse. He knew job ads were written to hire usually white, very academic, straight, able-bodied, financially stable…men. If I was a cactus in the Antarctic - they were roses in a manicured garden with full time gardeners. The landscape was purpose built for them.

At every job since, I have seen very few people like me. The few women in STEM I found were temporary interns and grads, or people who’d worked in tech longer than I’d been alive. Few of them were in positions of genuine power despite being leaders and mentors. Few of them were recognised for this work. They were hardy succulents, sapping up whatever sunshine was left underneath the leafy roses above.

This is by design.

When I fail to get that senior leadership role, it will be because I was a good woman. Too considerate, kind, empathetic. I will have listened too much and not interrupted loudly enough. I will be a bad leader.

When I fail to get that leadership role, it will be because I was a good leader. Too abrasive, strategic, powerful, and decisive. I will be a bad woman.

Like many women, I will decide whether to leave for a more hospitable landscape or to stay in the Antarctic.

I hope the Elevate program will be the hothouse in the Antarctic that helps me grow above and beyond the bottom layers, visible to others like me in the undergrowth. I will persevere to get that senior leadership role and hold myself and other leaders to account.

And more importantly - by the time I retire I want to see overgrown gardens, buzzing with bees and life. I want to have worked with diverse people who innovate out of necessity, ever adapting to the inhospitable, beyond the boundaries of what the manicured garden will support. “

Published on 24 November 2022.

ABOUT Tea, Tech and Trials

A place to blog the things I'm working on - from tech to infinity and beyond.

Kiowa Scott-Hurley