AI, Automation, Art & Aesthetics

All featured artworks drawn impatiently in MS Paint.

Published on 12 July 2023.

Context

In May this year I was invited to talk on a panel about AI at Scienceworks - for those who are unfamiliar, it’s a museum (or play-space, really) dedicated to science. I spoke alongside Linda McIver, Moojan Asghari and Holly Ransom - a formidable group of women who are absolute experts. We spoke about how AI will impact education, the climate, laws and regulations, data privacy…

One of the audience members posed a difficult question: how did we feel about AI and art?

I fumbled through my response - I’d been avoiding the discomfort I felt every time I saw an AI generated image, undoubtedly trained on unconsenting data.

One one hand…

- I’m excited to see more people generating creative outputs!

- I’m excited to use models to help me generate reference images for my own art!

- I’m thrilled to make ostentatious slide deck animations with minimal effort!

On the other hand… It’s disheartening to think about the artists who have spent years honing their craft and unique styles, only for their data to be stolen from them, and used to effectively replace them - all without credit.

I left the Scienceworks event pensive and apprehensive - I wasn’t ready to confront the elephant in the painter’s room yet.

A few weeks later, I was invited to speak on another panel - specifically because my interests intersect both art and AI. I was flattered - being recognised as an artist is always heartwarming given my paid work is all computers.

I also panicked. I’d really have to face this now.

In this blog post I’ll outline some of my thoughts about art and AI, but don’t expect me to solve any of the problems I identify here. I don’t think I ever will.

Becoming Obsolete

Lamplighters

My favourite book continues to be Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince. The novel is saturated with whimsy, from the childlike narration style and illustrations, to the futile and strange characters who inhabit each planet. Chapter XIV is 3 pages long, and visits a planet inhabited by a lamplighter. Over the years, the planet’s day and night cycle has grown increasingly short – at the time we meet the lamplighter, each day is only a minute long, and he laments that he must constantly light and extinguish his lamp.

As a modern reader this is exquisitely silly - imagine committing to such an absurd job! The lamplighting profession has been dead for decades now, and if I was stuck on a planet with the job of switching the lights on and off, I’d certainly have automated myself out of the job by now… or I’d have asked an electronics engineer to help me do it.

Old Treasury Museum

The Old Treasury Museum is currently running an exhibition about these since-obsolete professions, called “Lost Jobs.” It’s there that I learned in Melbourne, “The Metropolitan Gas Company employed 132 lamplighters in 1912. By 1933, there was only one left.”

An interesting theme that threads the exhibition together is the importance of the human beings who performed these roles. Whether it was the cheery impact of a tea lady, the harrowing realities for unwed mothers, or the simple fact that minimum wages were set for the purpose of raising families, the exhibition centres on what can only be described as the human condition.

The exhibition left me wondering whether my job was more parts human or technology, and whether a less human job somehow meant I’d stave off my own obsolescence for longer. I admit, it is a comfortable time in history to have the skills required to program our AI overlords. Some of the most human roles in customer service and creative thinking are looking unstable. For just a few examples I’ve seen in recent months…

- Wendy’s, Google Train Next-Generation Order Taker: an AI Chatbot

- BT to cut 55,000 jobs with up to a fifth replaced by AI

- Dropbox lays off 500 employees, 16% of staff, CEO says due to slowing growth and ‘the era of AI’

- IBM to Pause Hiring for Jobs That AI Could Do

Markets and Marxists

Robots will take all our menial jobs

So let’s talk about being replaced by robots.

With the release of ChatGPT, the average person is not only aware of AI - but they’re playing with it. They’re generating marketing material and editing their photos. They’re replying to emails with personal-tone-adjusted replies. They’re writing blog posts like this one with the help of LLMs to generate ideas. They’re making interesting music, summarising academic articles, generating stronger passwords… Everyone is using AI in a visible, and often well-branded way (think rising household names like Bard, ChatGPT, Adobe FireFly, Bing Chat, and so on.)

Of course, there’s an undercurrent of concern.

- If the robots can do my job, will I stop having a job?

- Will many people stop having jobs?

- If there aren’t enough jobs left in the world, what happens to my income?

- Am I fated to a universal basic income or to perish?

We’re forced to grapple with two possible worlds here.

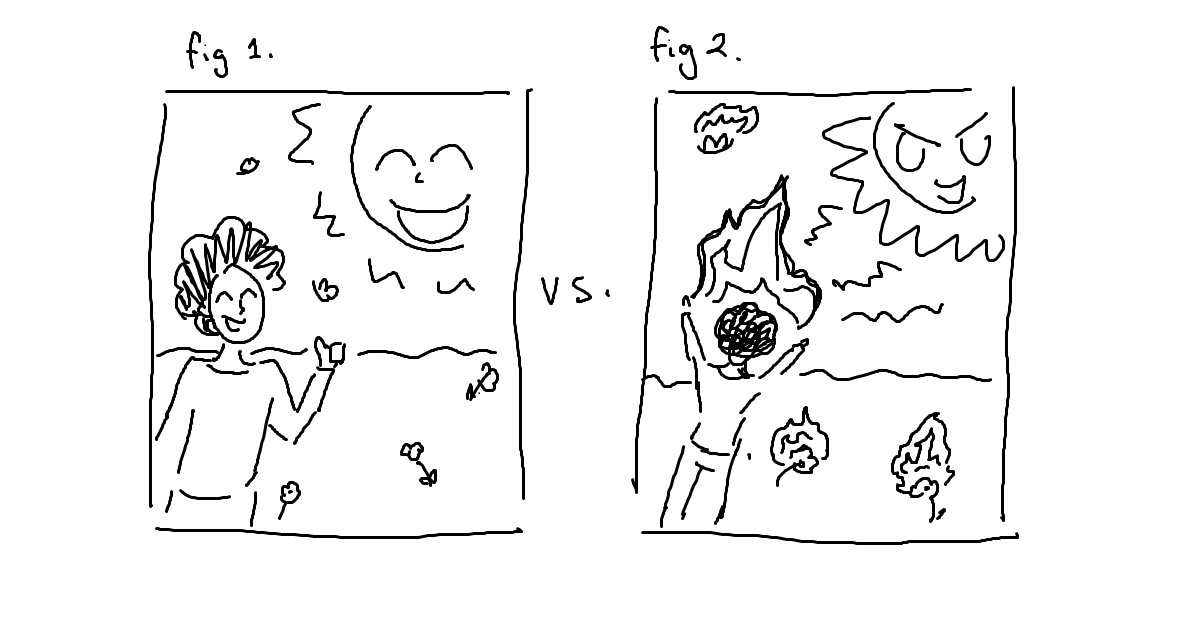

World One: The utopian version of this thought experiment leads us to believe we’re finally unshackled from the weight of our workloads, liberated by automation to pursue our passions, our relationships, our dreams. Being replaced by AI is an ideal outcome, assuming we can all still drink, eat, and be housed. Maslow’s Hierarchy and all that.

World Two: The version of this thought experiment which is cognizant of the neoliberal profit motive is far less positive. We have all observed how new technology and rising productivity haven’t resulted in increased purchasing power or a drop in working hours for the average person in first world countries. It is hard to believe that the creation of more capital (AI) will generate socialised benefits.

So while being automated out of work sounds like a dream… the reality is that we are afraid of the automated future.

Wait, robots will take our creative and fulfilling jobs too?!

Now, I don’t think most of us walk around terrified of being replaced by robots. We comfort ourselves: “I’ll find a job that the robots can’t do” or “the robots will just do the boring parts of my job anyway.” In some ways, we believe the advance of technology will free up more time for those tasks which are fundamentally human. The spreadsheets belong to the robots, but decorating the stakeholder presentation with cat comics? That belongs to me!

What is “new” with the advent of generative networks (that is, AI that can “generate” things like text or images), is a threat to something we thought was intrinsically human - creativity and the creation of new things. Mike Seymour of University of Sydney summarises the sentiment:

“The problem here seems to be that we thought that creativity, per se, was the last bastion, the line in the sand, that would stop machines from replacing someone’s job … I would argue that that’s just some kind of arbitrary notion that people had that caught the popular imagination”

Artists and the Dismal Science

I’m privileged to be an artist whose artworks are entirely for the fulfilment of my soul, not my bank account. For the class of artists who do depend on their art for income (income which is rightly deserved for creating value, mind you), what does this mean for the viability of their jobs?

To be clear, I don’t think art is a purely economic output - Marx himself once criticised capitalism on this basis, stating that “the dealer in minerals sees only the commercial value but not the beauty and the specific character of the mineral.” However, with the advent of generative AI, we are urged to ask questions like:

- Why pay a photographer for a stock image when a Bing AI can spit one out which has been trained on those photographs?

- Why pay a graphic designer when Adobe Firefly can do it all for me?

- Why pay an artist to design my album cover when I could hack it together with Midjourney?

To compare World One and World Two again here, I’ll define two ways artists make money.

The Corporate Artist: We pay artists to create visually interesting things to create economic value. If a shiny image makes me click on your webpage, then I’m also likely to see your advertising and generate revenue. A glance at popular YouTube thumbnails say everything you need to know about the attention economy.

The Economically Individual Artist: Art which isn’t created for business driven purposes is funded via means like personal commissions, buying merchandise, donating via KoFi… and a lot of what drives this engagement is a belief that what’s being purchased is unique, personal, meaningful. I pay for a portrait of my dog because it’s MY dog. I pay for a print of my favourite artists’ work because it is unique to them. The value of this uniqueness is codified in copyright law and exploited by NFTs.

In World One, we might imagine that artists are unburdened by corporate creations, freed to create whatever it is that they truly love and to build their own businesses.

But in World Two?

The Corporate Artist seems to be wholly threatened by AI, a concept explored well in this article. As someone who still obsesses over Microsoft Office clip art and its artists, a world without human-generated corporate art worries me. Could an AI have generated screen beans?

And the Economically Individual Artist? Well now an AI can work on my dog commission …and in a thousand styles, for free, in less than an hour. My favourite artist’s unique style can now be replicated with some key words, AND I can make them draw ANYTHING I want!

I have always envied professional artists and creatives - I’ve wondered how technically beautiful or ground-breaking my own art would be were I to practise it for 40 hours every week. I wonder what happens to the world when those jobs are taken away.

Photography and Sun Worship

This isn’t the first time a triumph in technology has threatened the creatives of this world - the 19th Century saw massive advances in photography, and with them, threats to the role of artists in society. If a camera can paint the truest possible representation of the world, what use is a technical artist or realist painter? In fact, why do we care so much about art anyway?

The Socratic Machine

It’s the 19th Century. God was dead and science had triumphed, filling the void.

In the Western World of the 19th Century, there was a rabid desire to accurately and precisely capture, record, catalogue, detail and understand the world around us - and cameras promised an unbiased method of capture. The outputs of science and technology were placed above all else, presumed to be superior, accurate, and most useful. We can see the same thing happening with AI now, where people blindly assume the machine generated output is correct, by virtue of being technologically generated.

In the modern day of course, we acknowledge all sorts of human involvement and bias exists in photography and actively exploit these qualities. We’re still collectively learning to identify and acknowledge this bias in machine learning model outputs - Linda covered this really well in a recent blog post.

Charles Baudelaire had some especially scathing remarks about the incredulity of replacing art with photography:

‘Since photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire (they really believe that, the mad fools!), then photography and Art are the same thing.’

And…

‘What man worthy of the name of artist, and what true connoisseur, has ever confused art with industry?’

Baudelaire had not imagined that photography would eventually be recognised as a form of art all its own, entirely distinct from the ravenous scientific purveyors of the time. Where scientists exploited the camera for its infallibility, artists exploited the extremely human characteristics of photography, evoking emotion and exploring new techniques and effects.

If the much-criticised photographer could become an artist, then what can we say of AI?

An Aesthetic Take on AI

The most challenging subject I did in my undergraduate degree was Aesthetics. The readings were brutally obtuse, dragging us unwillingly through the violent, the abject, and the sublime. The subject was one of the only times I’d seen art and beauty taken so seriously, with academic rigour applied at similar levels to what I’d seen in my pure maths subjects. I have a few thoughts about the aesthetic role of AI in recent weeks that I may as well add to this blog post.

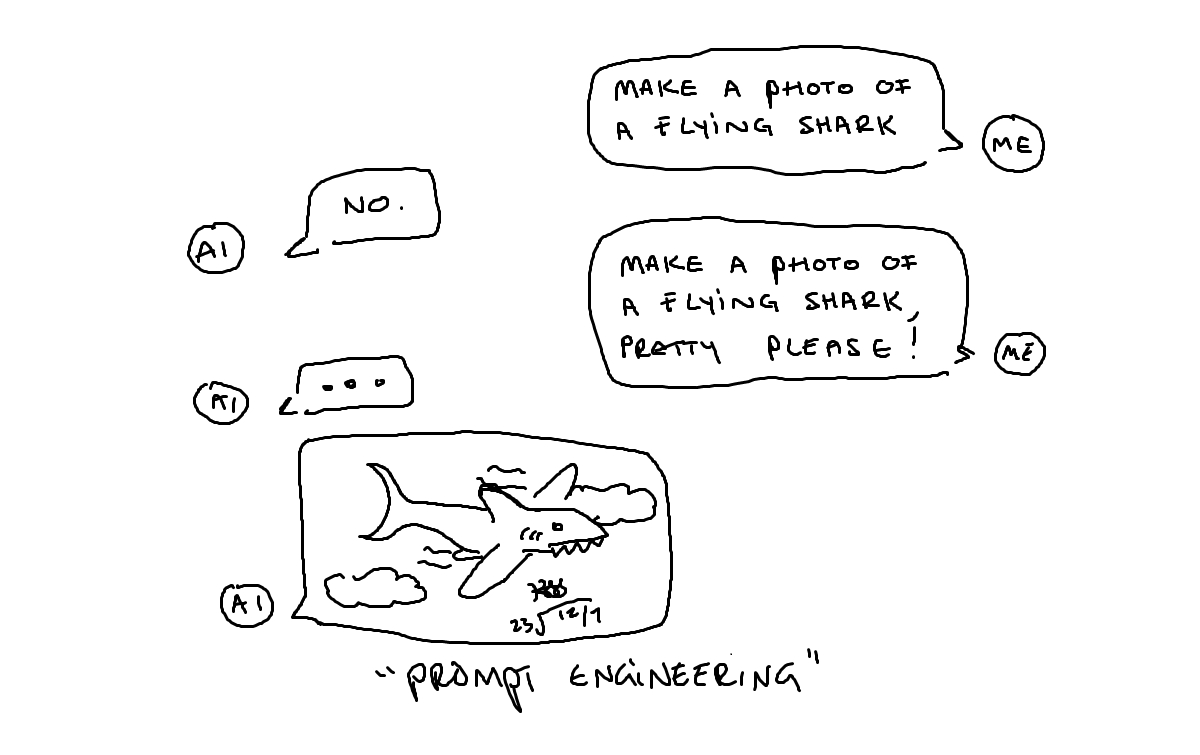

I’d like to propose that prompt engineering constitute a type of art, if you’re using the Nietzschean aesthetic framework. A few definitions…

…prompt engineering?

As many of us have discovered, half the battle with generative AI is crafting a prompt which generates the output we need. Many people have experienced the joy of a chat-bot hallucination, where it confidently asserts that 2+2 really is 7. One method to get around these bizarre results is to provide the chatbot with a worked example of a similar problem, and ask it to explain its answer step-by-step. This is one example of prompt engineering - writing better questions to improve the results generated.

On a side-note, I was recently nerd-sniped by a game which relies entirely on prompt engineering. The goal? Convince a chatbot to give you a secret password. How? Write increasingly clever prompts and exploit the qualities of AI to obtain the password. Given the sheer number of hours myself and my friends spent here, it’s clear to me that prompt engineering is an emerging skillset.

Back to Nietzsche

Right, so prompt engineering is all about writing AI prompts in clever ways. How could that constitute art? Having written a truly absurd amount at this stage, I’ll keep my thoughts here brief.

- Remember, God is dead for Nietzsche (and with that death, comes the death of an objective morality or truth to rely on.)

- Nietzsche was a firm believer that we could never really see the world around us in its truest state - it’s part of why he’s critical of the Socratic man in his writing. There’s a concession that of course we must act as though we can truly see the world for the sake of our own sanity, but there’s always a gap between us and the true state of things.

- If we can’t possibly understand the world around us, AND God is dead, then what is left for us? Well, for Nietzsche…

- “Only as an aesthetic phenomenon is existence and the world eternally justified.”

- Nietzsche is a firm believer that art justifies itself, and that it possesses a unique ability to remind us of how we construct the world around us and can never really see it - art uncovers to us our own self-deception.

- “We possess art, lest we perish of the truth”

- Prompt-engineering could certainly be considered a form of Art under the Nietzschean aesthetic framework - generative AI creates falsehoods, representations of the world around us that appear to us as real.

- Prompt engineers and AI developers remind us we are being deceived, that the creativity of the models are just piles of mathematics.

And so, interestingly, AI falls into the same space photography once did - all at once threatening the livelihoods of artists, conjuring debates about art vs science, and fitting neatly into the Nietzschean Aesthetic framework.

Wrapping up…

These are all the thoughts swirling around in my head when it comes to AI and art. I’m asking myself what the economic future of artists looks like, and whether it’s capricious to declare AI exempt from the status of “art” itself. You’ll notice I’ve left many things unresolved and I’m not sure I will ever resolve them. You’ll also notice I refrained from ranting and raving about the Apollonian and Dionysian despite having some good opportunities to do so - you’re welcome.

Music

And as a final congratulations for sitting through what has essentially been a ramble-post, here are some of my favourite tech-themed-beats.

- Youtube Playlist: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7SrOiqvqNyZvQ3lD79nYZo_7pix0F7m6

- Spotify Playlist: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7KmNAwGfIv9HuSWFGZEHYq?si=613d2526af2f4e91

ABOUT Tea, Tech and Trials

A place to blog the things I'm working on - from tech to infinity and beyond.

Kiowa Scott-Hurley